“Americans love a winner and will not tolerate a loser.”

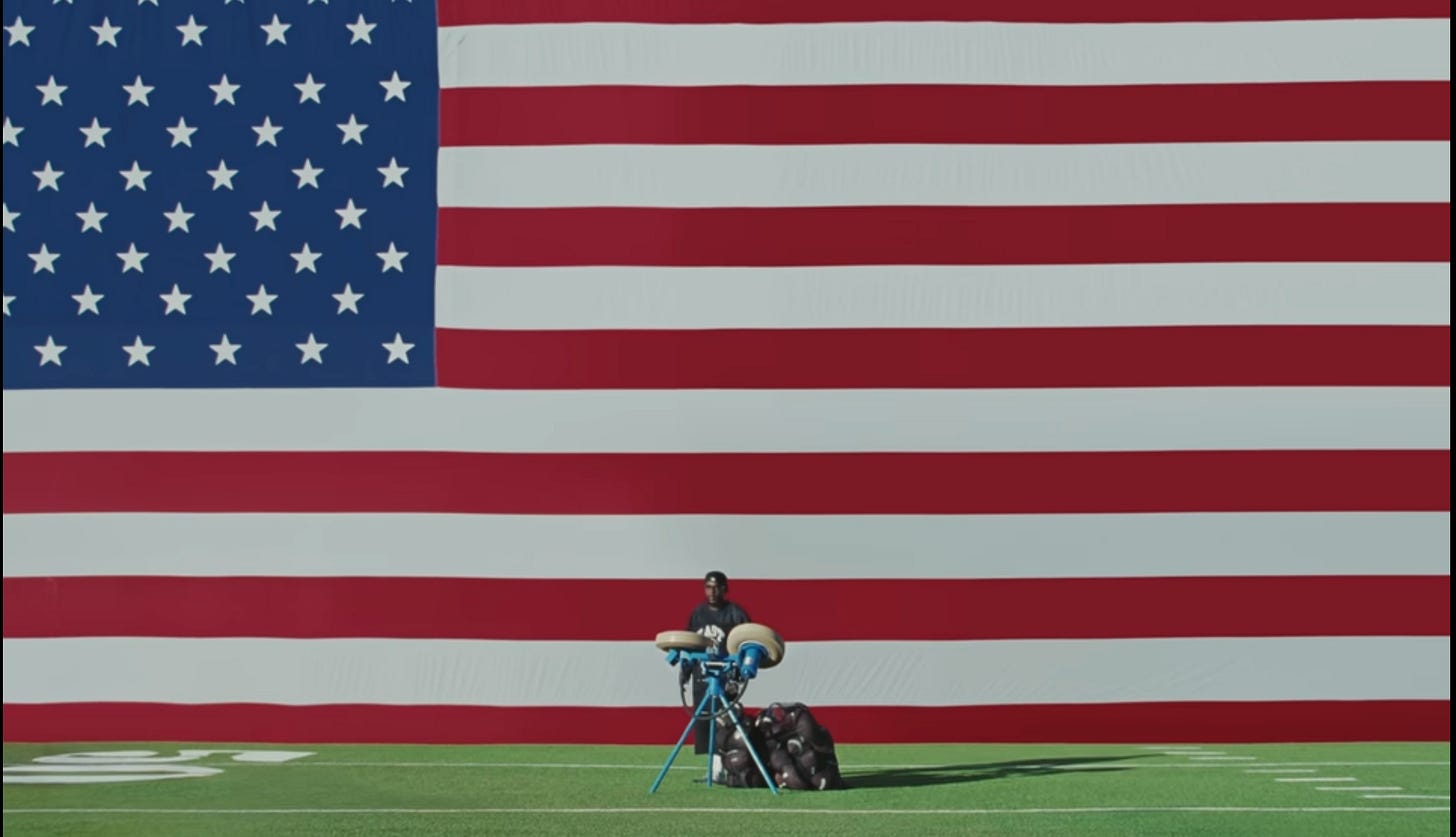

The fictionalized words of General Patton from the 1970 film “Patton” echoed through my cranium as I watched Kendrick Lamar announce his upcoming Super Bowl performance. Like George C. Scott playing Patton, Kendrick is placed in front of an abnormally large US flag, addressing the audience. “No round two’s”, Kendrick says, as a football shoots out at an unseen player. A nod, most likely, to his victory against Drake in their recent rap beef. Of course, the reference to Patton here is clear. He is the artist playing the Super Bowl, because “Americans love a winner.” The image is an example of the many coded references present in the work of Lamar.

Lamar exemplifies through his subtlety the importance of gatekeeping, not saying everything, leaving clues for the viewer to seek out, do their own research. The content is widely available, the songs are streamable, the videos watchable, but their message, their meaning remains encrypted. You need to know the reference to Patton to comprehend the full extent of the flex.

There is a strong tension for artist and creators between safeguarding culture and making it accessible and legible. Bear with me here, but the recent rollout of Charli XCX’s 360 music video encapsulates this tension.

I love Charli and her music. I’ve been bumping that since Pop 2. However, the “360” music video is an example of culture portrayed as something to be put on display, fully visible. Julia is everywhere, she is in the business of ubiquity. There is nothing cryptic about being “brat”. The implication here is clear: there are influencers and it-girls to follow (they are in the video!), places to frequent, podcasts to listen to. “Bratness” is not gatekept, it is accessible through consumption.

In stark contrast stands Kendrick Lamar's Not Like Us, a work that, while highly popular, draws a distinct line between public accessibility and cultural encryption. On the surface, anyone can listen to the track, understand the lyrics, and even dance to it. But there’s a deeper layer that’s reserved for a specific community, notably people from Compton. The symbols and meanings Kendrick weaves into the video are encrypted—they require deeper engagement, context, and understanding that’s often only available through presence in that cultural context or deep analysis and research (see the many videos breaking down the symbols in the Not Like Us music video). It's a coded language, and not just anyone is given the key.

The video opens on Compton City Hall, a site familiar to those who have been there, but unknown to those who have not. There is Tommy the Clown, the legendary figure in the LA dance scene, who appears in the video’s third scene. There is the room where Kendrick does the push-ups, first a nod to Drake’s diss but the room’s design is eerily similar to the room Milla Jovovich was photographed in 1997. Milla was infamous in the 90’s for appearing nude at age 15 in the 1991 film “Return to the Blue Lagoon” and was discovered by Jean-Luc Brunel, who was accused of allegedly supplying girls to disgraced financier Jeffrey Epstein. (The Guardian, 2022). The 16 push-ups. The puerile hopscotch. The repeated appearances of crip walks, which originated in Compton.

These are two very different modes of cultural interaction. Charli’s approach invites participation: the memes exist for remixing, the portrayed scene and its participants exist to be followed and engaged with on social media—the culture of Brat is open and participatory, giving anyone a ticket to join the global digital party. Kendrick, on the other hand, erects a metaphorical gate, around hip hop and black culture, emphasizing that some aspects of the culture are not for everyone. To truly belong, to truly get it, you need to be from a specific place, rooted in a unique culture. Kendrick’s message in Not Like Us is more profound: this isn’t something you can just buy into. He’s speaking to Drake, but also to us, the wider audience: You can’t just mimic this culture. We’ve been accustomed to fluidly entering new subcultures, claiming appartenance left and right, shifting shapes digitally. Lamar is adamant: You have to live it, be born into it, breathe it. Some things are not for sale, not for show. There’s an essence in certain communities, in certain experiences, that cannot be replicated. This is what he’s reinforcing: “You are not like us, and you never will be like us.”

Few figures are as reviled in our modern cultural landscape as the “Gatekeeper”. Called pompous, haughty, pretentious, the gatekeeper excludes and hoards. The gatekeeper prevents the free flow of information. The gatekeeper is greedy in a world where sharing a link is free.

My friend Raihan, a notable foodie, loves this copypasta.

i find mfs like u really interesting bro. i ain't gon lie this spot is kinda like a personal thing to me you get what i'm saying. it's just like a personal vibe u feel me. what's really crazy is you wouldn't even wanted this if u ain't see me post it u get what i'm saving. i don't even think u really hungry like that tbh bro. so go ahead find yourself something to eat bro go open your fridge bro this not the fridge this the internet u get what i'm saying. this shit taste insane though shit wild seafood pasta uk what i'm saying this shit market price u feel me shit i wish i could put u on but its really a personal vibe u know. i bring my loved ones here so u know what i'm saying u be easy bro

This copypasta can be interpreted through René Girard's theory of mimetic desire. René Girard (1923–2015) was a French historian, literary critic, and philosopher of social science.

Girard's theory posited that human desire is not autonomous or self-driven but rather imitative. People desire things because others desire or possess them, not because of the inherent qualities of the object itself. In this copypasta, the speaker implicitly accuses the other person of wanting the seafood pasta simply because they saw the speaker post about it, thus initiating a mimetic cycle of desire.

As Girard writes, “Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires.”

Or as Frank Ocean reminds us, “Niggas love to steal”.

The “personal vibe” in the text is important. The speaker positions the meal not simply as someone that is consumed but rather something to which there is a personal, emotional, and potentially, as it is frequent with food, a cultural value. They act as a gatekeeper, preventing access to someone who is perceived as merely wanting to consume out of mimesis and not out of a desire to cultivate this personal vibe. To extend this reading, if they had cultivated this personal vibe, say a love of seafood, they probably would have found this place already. The speaker introduces friction to access, a cultural repellent to what Chapman calls in his 2015 analysis of scenes “sociopaths”, cultural extractors who capitalize on scenes and subcultures for their own personal gain, financially and cultural. Lamar would call them “colonizers”.

The Office of Applied Strategy sent me their upcoming dossier called “Hyper-Optimization” and the theme of friction recurred throughout and seems very applicable to the role of Gatekeeper.

The writers define “hyper-optimization” as the “event horizon before which we can no longer control the speed of culture because it has become frictionless.” They add a quote by Creative Director Phil Chang, “Culture is what emerges as a product of the friction between people and ideas. Friction […] is what makes culture exciting to begin with.”

The Gatekeeper is important because they provide the friction. The Gatekeeper is not truly exclusionary, rather they introduce labor to access the culture, they introduce a rite of passage, of initiation. The gatekeeper creates the fence which the enthusiast happily hops and stops the dilettante.

The clues area actually all there for you, the enthusiast, to find. Go to the place, meet the people, live there. The Gatekeeper is the reminder that culture requires labor and that access is not a right, it must be earned.

Now, you know how I feel.

That’s all.

In total agreement. Wrote this a few months ago:

The Other Side of Gate-Keeping

Viewed one-dimensionally, the other concept that requires clarification is gate-keeping. Only seen to be a fence, its hinge is forgotten. A gate is the passage between interior and exterior, from one space to another, private to public, mine to another's. It is both about keeping out and allowing in. The current conception of “gate-keeping” is exclusionary, cast aside its ability of letting people in. It is just as much about blocking someone’s presence as cautiously permitting entry. Whereas a fence is defensive, a gate is where defensiveness can fall — where trust is tested. Gate-keeping is yes about exclusion — you can’t sit with us — but also the process of self-protection, of deciding who enters your “home,” where you let your guard down. Selective in either instance, one establishing a hierarchy and the other an intimate gesture — exposing one’s vulnerabilities and potential weaknesses. A gate is an architectural reminder that you’re entering private grounds, sacred space. In an era where we constantly share our lives, gatekeeping can facilitate calm and intimacy, where one can make mistakes and embody eccentricities without worrying about others’ eager eyes, their judgements. Stepping through the threshold via a gate is a reminder that someone else’s world is precious, not to be publicized on your terms — you’re in their home. This second dimension, the empathetic cousin of privacy, deserves recognition, as well.

Love the use of Charlie and Kendrick as symbols on opposite of the gatekeeping axis… love a return to exclusivity, gatekeeping etc. we’ve veered too far into making every accessible for all to enjoy. Some things take, and demand, effort to enjoy. Effort doesn’t guarantee success or enjoyment but I don’t think anything is worth exploring without that effort, that friction.