Do not wear your new seemingly Chappell-Roan-inspired Harris-Walz camo hat to Zimbabwe or you will get arrested. It is one of the 19 nations where wearing camouflage clothing is prohibited. One of the 19 nations where camouflage has retained its original connotation as a military garment and thus is strictly restricted to military personnel. In most countries with militaries, to this day, the donning of official battledress without having served is deemed “stolen valor” and is frowned upon.

This hat is, of course, not official battledress, unless you count the Culture War. And camouflage has, in most Western countries, now entered the realm of fashion and has spread its utility from military to other activities like hunting.

But why did the Harris campaign choose this specific design? Why camouflage?

Since the viral MAGA hat in 2016, Democrats have failed to produce any commensurate hat design to rival the memetic power of Trump’s red hat. The 2020 hat had a vintage appeal, leveraging a simple serif with large and small caps lettering, but did not hit. The 2024 version also remained a tad lackluster, the typeface was modernized to a bold sans serif, with a stylized “E”, almost in an attempt to emphasize the new, a counterbalance to the age concerns that plagued the ex-presidential candidate.

The new hat employs a narrower bold sans serif, set in bright orange, atop a RealTree style camo. It has apparently sold out in minutes upon release.

The first instance of camouflage was used by hunters to conceal themselves from their preys. They covered themselves in fur, leaves and mud in order to avoid being spotted by the animals they were hunting. (Newark, 2013)

The type of camouflage used on the Harris-Walz hat is RealTree and mimics a similar method of concealment with nature. It was commercialized by Bill Jordan and his company, Realtree, 1986. Used usually by hunters in nature, Realtree can be spotted in rural areas worn by off-duty hunters

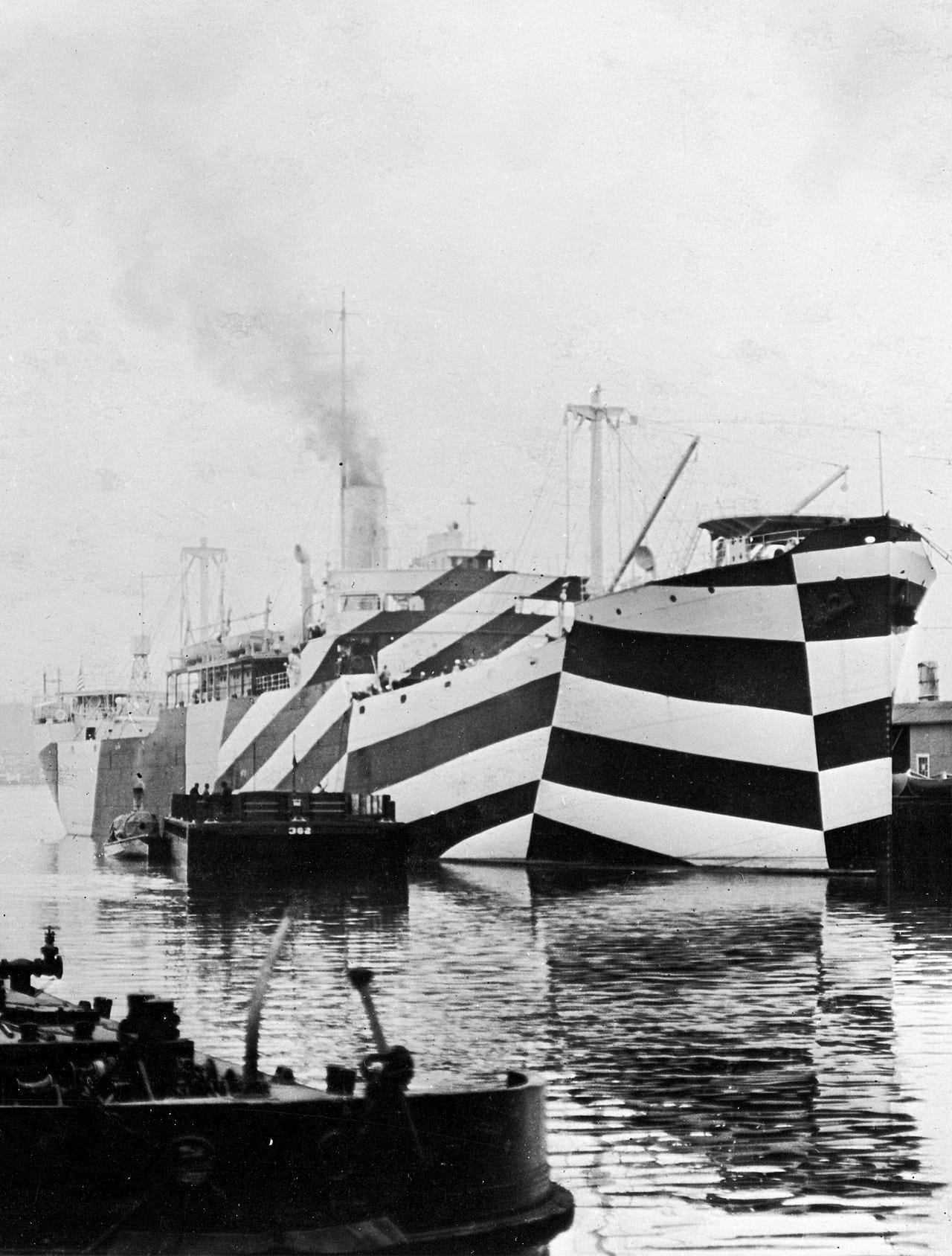

During the First World War, aerial photography allowed enemy planes to fly over areas with trenches, spot targets and later attack with precision. In order to abate visibility, armies developed camouflage or patterns that were hard to discern from above.

The phenomenon of counter-shading for concealment was first identified by the artist Abbott Thayer, the “father of camouflage”, in 1892 and later introduced to military practice in 1898.

Camouflage, as we know it, was first developed in France in 1914 by artist Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola. The artist painting “camouflage” was known as the “camoufleur” hence the name.

We can pinpoint the first intersection of military camouflage and civilian fashion to the Dazzle Ball of 1919, held at the Royal Albert Hall in London, which celebrated the end of the First World War. Art students designed clothing inspired by the naval “dazzle camouflage” of artist Norman Wilkinson.

Already camouflage had a counter-cultural weight. We observe a second resurgence in camouflage in the 70s during the protests against the Vietnam war. The Vietnam War was notably televised, a first at the time. This constant broadcasting of the brutal images of warfare divided the nation and helped spur the anti-war movement, who appropriated the depicted garb of soldiers during their protests.

“The horrific images of war that were brought to the American public during the Vietnam war ensured that the wearing of camouflage by war protestors was sure to be controversial, and laden with connotations and associations. This coupled with the fact that it was, and still is, a felony to wear any distinctive part of military uniform, meant that camouflage was very powerful clothing for protestors to wear.”

Ronan Dillon, curator and artist

The pattern migrated culturally from artists (Razzle Ball) to protestors (Vietnam Veterans Against the War, 60s/70s) to skinheads to counterculture (rap, punk) to mainstream fashion to now a mix off-duty hobbyists and fashion enthusiasts.

As a symbol, camouflage’s function differs based on the location where it is worn. In an urban setting, the camouflage’s utility disappears, instead of blending in, as it does in nature, it clashes with the concrete, glass, and lack of greenery of the city. Its function is inverted. One wears camo to be seen. It usually conspicuously signals participation in war, hunting or outdoors activities where the garments are required. A second inversion is the re-appropriation the symbol by the children of people who did participate in the activities. The style is worn in urban settings as a reference to their upbringing. (Chappell Roan is probably somewhere between the first and the second.) A third inversion happens when it is worn by people who do not participate in the related activities. Camouflage is deployed, in this case, as a mere pattern, a loose reference to military style, usually paired with combat boots and bomber jackets, as a nod more to punk subcultures than to soldiers. See Raf Simons’ youth-focused FW 01 collection “Riot Riot Riot” and its highly desired bomber.

Is the Harris campaign signaling a rugged Middle America sensibility? Plausible since some of the battleground states rank fairly high in Google Trends for “RealTree camo”, Wisconsin (11), Georgia (13), North Carolina (18), Pensylvannia (24), Michigan (26), Arizona (44), and Nevada (46).

The last major spike in camo happened after 9/11, as wearing it became a show of patriotism. Camo is loaded culturally, symbolizing either a state of leisure (for hunting) or a state of war, through either resistance or embrace.

In urban areas, the camouflage hat will paradoxically stick out. Amidst the black and navy caps usually worn, its “camo” pattern may be hyper-visible and realize its memetic goal of rivaling the red hat.

What will it signal? Leisure? A symbol of newfound patriotic unity? Counter-cultural resistance to war? Or simply, that its wearer is in the trenches of the Culture War?

Time will tell which Inversion we inhabit.