The culture writers have been lying to you, again.

“Indie Sleaze” never happened.

I was there, front row at the Hot Chip show, thick sweat oozing out of my skinny jeans, listening and grooving to the live renditions of the songs from “Made in the Dark” (2008). Alexis Taylor crooned over buzzing drum machines, donning the bright colors emblematic of the era. I was bumping into fellow hipsters in dark denim and neon American Apparel V-necks, some with surreptitiously lit J’s inside of the venue.

Just kidding. I was thirteen, living under the tyranny of a draconian curfew. But doesn’t that sound believable?

In a present where novelty seems to have ceased, where all we seem to encounter are recycled aesthetics, we long for unremembered pasts so much, that we fabricate them.

In fact, upon thorough research, there was no such thing as “indie sleaze”. The term “indie sleaze” does not appear in Google Trends until March 2022. Looking closely at the history of the Wikipedia article on the topic, we can identify that the post was created in August 2022. The simultaneous post in the “Aesthetics Fandom” Wiki is from December 2021. A closer Google Search for the term shows no presence online from 2000 to 2020. The term “indie sleaze” is a very recent fabrication, an attempt to rebrand the past in order to render it marketable. To sell it to you, the authenticity-hungry Zoomer, the nostalgia-ridden Millennial.

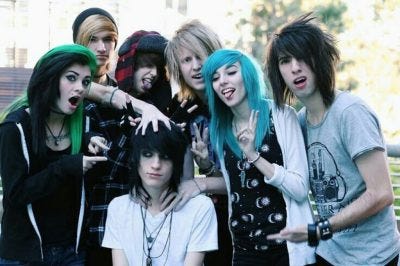

To be specific, the eclectic stylistic elements we now ascribe to “indie sleaze” existed between the mid-aughts and the mid-tens. Hedi Slimane (whose tenure at Dior Homme cemented “skinny” as the go-to silhouette for jeans), Pete Doherty, and Alexa Chung are good examples of a part of that style. Cool kids mixed 90’s grunge, rocker debauchery and smudged makeup. There were raunchy dance parties like the ones hosted by Misshapes in New York and the ones photographed by TheCobraSnake that captured the scene and the clothes worn at the time. This eclectic fashion became emblematic of the counter-culture of the 2000’s, but this was not a cohesive aesthetic. There were hipsters, and this niche group itself split into “indie”, “twee” and “scene”, amongst many other categories. These labels encompassed a broad spectrum of styles and attitudes that were characterized by a DIY ethos, a love for alternative music, and a rejection of mainstream corporate culture. But these labels were fluid and semantically loose. The term “indie sleaze”, again, was never used.

Part of the popularity of the styles at the time was driven by social media like MySpace. Misshapes recount in an interview in W Magazine that “the group posted the photos online, hoping that attendees would use them in their Myspace profiles, but kids across the globe soon started pouring over the galleries for style inspiration.”

“Scene” was another term that was popular at the time, particularly among younger individuals who gravitated towards more vibrant, eclectic fashion and music choices. The “scene” style was often characterized by bold colors, graphic prints, and a mix of punk and emo influences, making it distinct from the more subdued, retro-inspired hipster aesthetic.

“Twee” refers to a subgenre characterized by its overtly cutesy, whimsical, and nostalgic sensibilities. It embraces a delicate, often childlike innocence, with a focus on vintage fashion, handcrafted items, and a love for the quaint and kitschy. Twee is marked by an appreciation for the simple and the sweet, often manifesting in pastel colors, floral patterns, Peter Pan collars, and an overall sense of earnestness that contrasts with the more ironic and edgy aspects of hipster culture. While both twee and hipster aesthetics share a rejection of mainstream culture, twee specifically romanticizes a bygone era of simplicity and charm, often drawing inspiration from mid-century style and pop culture. Zooey Deschanel remains a twee icon.

According to literary critic Frederic Jameson, in postmodernity, the past is not experienced directly but rather through a set of stylized representations. When current cultural production lacks originality or fails to resonate, there is a tendency to look back nostalgically, selectively reviving and reinterpreting past styles and movements. This nostalgia, however, is often more about our current discontent than a true reflection of the past. This nostalgia is aided by our technological platforms like Tumblr which was particularly popular with the indie crowd near the tail end of “indie sleaze”. In my 2021 talk “A Foray into Tumblr-core”, I note how “Tumblr is a backward-looking platform” and how “the nature of the site breeds nostalgia”. Writer Shannon Howard in her essay “Everything Old is New Again” describes the platform as being driven by the “forwarding of ideas rather than original conception.”

Tumblr posts tend to be reblogs or reposts of previously posted content that one curates for their page. The blogger generates authorship from the act of selection, or “curation”. This act enables the blogger to reframe images and texts and make them their own through meta-commentary. Tumblr seems by design captured in the constant act of stylized representation, the hauntological weight of the “reblog”, the forever repeating of aesthetics.

The resurgence of interest in "indie sleaze" can be interpreted as a new manifestation of this dynamic. As contemporary fashion and culture have become increasingly dominated by hyper-curated, algorithm-driven aesthetics, there has been a yearning for the perceived authenticity and rawness of the indie era. In the same interview, Misshapes hypothesize that “indie sleaze” is seeing a resurgence because “It really was extremely authentic—the way that we dressed, the way that we partied, the way that we went out. I think there’s obviously a little bit of a nostalgia for that.”

The grainy, lo-fi photography, thrift-store fashion, and gritty, DIY music scenes of the mid-2000s are now idealized as a time of unbridled creativity and rebellion, despite the fact that, at the time, these trends were often met with ambivalence or even disdain. (People notably derided hipsters and blogs like Gawker made fun of the Misshapes party images). We mine the past for inspiration instead of spinning up new styles. We mined “Y2K”, and now we mine “indie sleaze”.

This romanticization, however, risks oversimplifying the complexities of the era and the subcultures within it. At its extreme, the risk is a mischaracterization of the past. A categorical error where we assume that the new labeling of the past accurately maps to the trend of the era. We mistake the modern label as historical fact.

It also reflects a broader cultural anxiety about the present moment—a sense that, in the face of rapid technological change and a homogenized global culture, we have lost something vital that can only be reclaimed by looking backward. In this way, the resurgence of “indie sleaze” is less about a genuine revival and more about our ongoing struggle to find new meanings and new identities that can usher us into an uncertain future.

The past is cozy and lined with certitude. “Indie sleaze” is a comfortable aesthetic blanket for an uncertain time.

Why then is the term “indie sleaze” so popular now? To frame a style with a label is to make it marketable. The labeling of loose cultural artifacts into a cohesive whole is not in service of history but rather in service of commerce. When the term “indie sleaze” becomes popularized, the past is rewritten and suddenly the weight of its authenticity can be re-sold to modern audiences. Suddenly, it becomes a hashtag on Depop. Suddenly, it becomes the name of a playlist on Spotify. Suddenly, it describes something we can buy into. The labeling is not historical, it is commercial.

I’m sure the aughts and tens were a lot of fun. Skinny jeans were definitely worn. It is important however to be mindful of the past’s re-presentation of contemporary social media and its incessant rewriting in the service of SKU’s and merchandising.

Please don’t make me watch Skins again and, most importantly, don’t let culture writers lie to you.

Indie sleaze is a coined term in the broadest sense, like hippie or other subcultures that are discussed after time of the ending. As someone who lived through this time, of course it’s not a term anyone used during then because that’s never how these movements were analyzed prior to current day with an influx of aesthetics rather than rooted subcultures. It’s generalized because that’s all that people can do who didn’t live during the time or know much about it. I don’t disagree, because of course it’s a marketing tool, but history often generalizes and lumps multiple groups and sub groups into one category that doesn’t make complete sense.

Subcultural groups are dead. Ive been watching old interviews of punks, mods, rockers, skinheads, and gay subgroups from the 60s-90s, and those categories absolutely don’t exist anymore. They were treated as circus freaks/ non-conformists by the traditional media at the time. But importantly these groups of individuals were resilient, rebellious, had a strong sense of community, politics and identity.

But Zoomers nowadays are too embarrassed to fully embrace one subs culture, it would be ‘too cringe’ or ‘trying too hard’. Instead, in postmodernity these eras have all been blended into one. The clothing fashion styles and the hairstyles are amalgamated into one ‘cool’ style.

The groups of people who dress in this new style all really represent/ stand for the same normie, conformist ideals. They don’t have a political identity behind their aesthetic identity, there’s no substance or culture beneath it, they just thought it looked cool on a mood board.

The millennial tumblr aesthetic & Brooklyn hipster aesthetic (circa 2010-2016) is kind of a re-imitation of skinhead fashion in the 1970s and 80s; rolled up skinny jeans, tucked in polos/shirts, suspenders, Dr.Martens but mixed in with modern elements such as beards, man buns, branded clothes. The tumblr/brooklyn hipsters didn’t listen to rebellious music, they weren’t oppressed by society, they weren’t punk rock. Their aesthetic was fulfilled by oat milk lattes, buzzfeed articles and by owning small dogs.

The new zoomer aesthetic is a re-imitation of late 90s, early 2000s hardcore skater culture. Baggy jeans, drop shoulder graphic tees, striped adidas shoes, mixed in with mullets, moustaches and short shorts from the 80s. The clothes aren’t ‘vintage or charity shop’, they’re expensive remakes of that style. Most zoomers are too embarrassed to get into a hardcore mosh pit, and would hate the idea of their phone being knocked out of their hand as they cannot film it. Rigid, stiff, sexless and allergic to dance.